The UMWA sought to achieve industrial stability in coal mining from the union's earliest days. In the best light, this meant restricting competition between the operators and winning legislation that restricted or outlawed child labor, defined what a legal ton of coal was, required safe mining practices and workplace safety, insured mine workers' safety and health, and provided for mine workers after they were too old or infirmed to work. In the early days the union and the coal operators sought to reach agreement on coal prices together and to use their relative power to control coal markets together. But the operators were never good partners to the union, and competition from non-union and low-cost mining districts and industrial monopolization worked against union-operator cooperation. Industrial chaos was always just a half-step away. Under these conditions, then, the union and the operators came to represent different and opposing interests.

In the worst light, local and district unions competed with one another and the union's leadership played union locals and districts against one another. The leadership sometimes sought to partner with certain operators and politicians in ways that were at least unethical and that did not always serve the worker's long-term interests. Corrupt union officials have done much damage to the union's cause and reputation. The union was sometimes fighting for industrial stability on its own. Mine workers often looked first at their mine, then at their company or region, and then, perhaps, at the national picture when it came to union affairs and deciding union policies and voting on union contracts. Changes in mining technology worked against the mine workers maintaining employment and solidarity and keeping control of their work, and resentments have grown from this. The noble attempts by the union to win industry-wide contracts and to create a working pension system and to provide for healthcare have depended on extending union organizing, stable employment, payments made by union-represented coal operators, industrial stability, fair courts, and cooperation and support from state and federal officials. Only at rare moment in our history have most of these factors been in place at the same moment.

It is a miracle and a blessing that the UMWA still exists. The coal operators and their allies have sought to divide the mine workers and have used their economic and political power to isolate the workers and break the union. They have brought extraordinary pressure to bear against the union and have used violence when that suited their needs. They have influenced the public schools and other public institutions in many areas to be "pro-coal," which has come to mean pro-company, and the true history of mine workers' struggles has to be constantly rescued from their hands.

The union remains the only reasonable and available institution to represent mine workers' interests. There are about 67,000 coal mine workers in the United States and Canada, and the UMWA may represent something just over 20 percent of those workers. According to the union's website, the UMWA now represents "coal miners, manufacturing workers, clean coal technicians, health care workers, corrections officers and public employees throughout the United States and Canada." Not too many years ago the union had the slogan that "God, guns and guts built the UMWA" and I believe that that has been true. The UMWA has set a high bar for other unions and has used its power to support other unions. The idea that strikers have to "last one day longer" and our modern concepts of industrial unionism come from the UMWA to a great extent. Today the union depends more on God and guts and its ability to make its case to workers and its power to win good contracts.

We need a new era of union organizing to boost the union's numbers and influence and power so that mine workers do better and so that their communities survive. Good living wages and retirement benefits, guaranteed by a union contract, circulate through mining communities quickly and raise everyone's standards of living. A progressive wage floor, strong health and safety provisions with active enforcement, and protected pension plans in coal mining benefit all workers and our communities no matter what jobs we have or where we live.

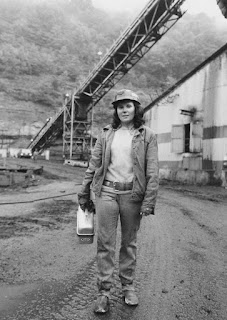

The pictures and music below come from a variety of sources and are posted here to show readers something of mine workers and mining communities. I am including some of my own narratives and commentary by others. Not all of the workers and mines here are union-represented. My point is to create a context for understanding where the UMWA comes from and why the union is needed now.

The best resource there is the United Mine Workers of America website. One of the best things that you can do right now is to support the striking Warrior Met mine workers in Alabama. They have been on strike for over 21 months. Go right here to do that. Another great resource for learning union history is the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum. The Mother Jones Museum is also a great resource.

Built in 1921 for the African American community of Tams, West Virginia. The New Salem Baptist Church is one of the last remaining structures in Tams. At one time the church boasted a congregation of around 350, but those numbers have dwindled to about a dozen since the mine closed in 1955. The last residents of the town of Tams vacated in the 1980s and the remaining structures were destroyed or moved. Photograph and text by David Dunlap, courtesy of Broken Doors Photography and Art Collective

New Salem Baptist Church

Built in 1921 for the African American community of Tams, West Virginia. The New Salem Baptist Church is one of the last remaining structures in Tams. At one time the church boasted a congregation of around 350, but those numbers have dwindled to about a dozen since the mine closed in 1955. The last residents of the town of Tams vacated in the 1980s and the remaining structures were destroyed or moved. Photograph and text by David Dunlap, courtesy of Broken Doors Photography and Art Collective

A snapshot of War, West Virginia.

Incorporated in 1920, War was previously known as Miner's City. At its height War had almost 4,000 residents, a far cry from the approximately 690 as of the 2020 census. Photo and text by David Dunlap, courtesy of Broken Doors Photography and Art CollectiveBlue Diamond Mines--The Johnson Mountain Boys

1973

An anthracite miner and his wife

A coal mining community and family in Utah

Women gathering coal in the Pennsylvania anthracite region.

Photograph by Kristen Kennedy of Virginia Lee Photography. She is one

of my favorite modern photographers and her work has appeared on this blog many times.

The Monongah Mine Disaster of December 6, 1907 took the lives of at least 362 mine

workers, many of them immigrants. It was the worst disaster in coal mining history in

the United States.

"The coal you mine is not Slavic coal. It's not Irish coal. It's not Polish coal. It's not

Italian coal. It's coal."---John Mitchell, President of the UMWA 1898-1908

Around the time that Arnold Miller was becoming nationally known I decided that I would

go to work in the mines as some of my great uncles and others in my extended family had done. I was close to dropping out of school, and working in the mines was all that I could see myself doing. My father, who knew the miner's life, and I had quite an argument about it. The argument ended with me saying arrogantly "I'm going to work in the mines!" and my father saying, "Just stay where you are. I'm going to go find a heavy object and kill you and save the company the trouble." I waited until after my father passed on to get my mining papers.

On April 20, 1914 Colorado National Guard troops opened fire on the Ludlow tent colony in Ludlow, Colorado. Striking mine workers and their families were living in the tent colony during one of the most dramatic and heart-wrenching strikes in U.S. history. At least 19 people, including 12 children and 2 women who were associated with the strikers and the union, died that day at Ludlow. This is a photograph of the Ludlow Massacre memorial.

Nimrod Workman - Forty-Two Years (1976)

Afterword

The "Blue Diamond Mines" song may seem like an odd choice to open this post with, but I believe that it captures a feeling of a place and time and allows me to say something about mine workers' cultures. There are plenty of complaints made by mine workers about the union, but in my experience these are complaints about policies or personalities more than anything else, and they're often made from a place of love and hope. Dissent was baked into the union when it was founded in 1890.

I believe that I owe the UMWA for almost everything that I have today, and I feel good about paying my associate dues every year. How and why I'm paying associate dues instead of retired dues is a long story, but life has its twists and turns. I feel especially good when I can support the Black Lung Movement. I'm thankful every day that I have known so many mine workers, had them as friends and family, joined those picket lines, shared time and food and memories with them and their families. They blessed me with their wisdom and humor, blessings that I have not deserved. Regardless of what you think about coal and energy sources and climate change, I'm sure that you believe that mine workers should receive decent pay and benefits and have secure healthcare and retirement systems. I'm sure that you believe in workplace safety and health. I'm certain that you believe that coal communities and former coal communities should not be abandoned and left to fend for themselves.

Please support those Warrior Met strikers. Please support the miner's rights to a fair standard of working and living, to dignity in retirement and to healthcare. Please support the coal mining and former coal mining communities.

No comments:

Post a Comment