Black Diamonds: A Childhood Colored by Coal by Catherine YoungTorrey House PressPublished: 09/26/2023

Pages: 288

ISBN: 9781948814836

$17.95 paperback

The Lackawanna Valley is a c. 1855 painting by the American artist George Inness

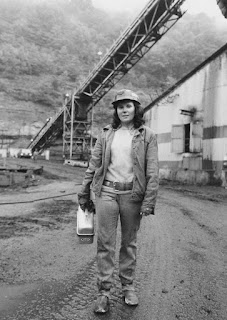

Catherine Young has written a marvelous "personal geography" out of her raw experiences growing up in Scranton, Pennsylvania in the final years of anthracite coal mining and manufacturing in Northeastern Pennsylvania (NEPA). As she says in her Afterword, "...the story connects humanity's choices around the globe. I wrote it to honor a people and a history I felt had become lost, and I wrote it as a way of understanding the choices before us."

Young uses the painting above as her point of departure and gives readers a child's perceptions of life in Scranton, then near the northern tip of the active anthracite coal fields. The book is filled with the innocent questions children ask and the answers given by adults and the memories of walking with her parents through her hollow and through downtown Scranton as the city fell apart. She recalls smells, tastes, sounds and other sensations with complete accuracy. She gives a tragic and stunning account of trying unsuccessfully as an eight-year-old to save her father's life, but this loss of a parent does not stand alone as the book's saddest moment because there is so much other loss recorded here: the insults of people not from the region directed at the people who live there, the loss of civil society and jobs, the loss of a familiar environment, the loss and altering of the region's environment for mining and railroads and highways, and Young's leaving the region as a young adult.

I know a good deal about what Young has recorded because my father's family lived in the Hazleton area, about one hour south of Scranton. She and I are about the same, age, I think, and I expected in my teenage and young adult years to live in the area, work in the mines or factories there, and retire and die there and be buried alonside of my relatives in a quiet cemetery in Weston. It didn't work out that way for me, but I clearly remember the smells, sounds and tastes that Young describes.

Young is absolutely correct when she writes about the mass depression and hopelessness that has taken hold in NEPA. That grim lack of hope likely set in during the early years of the 20th century and deepened over the decades. The region has been exploited by the coal and manufacturing companies and crooked politicians, wounded by union failures, beset by environmental crises that seem irreversible, and has more recently has been overwhelmed by drugs. These are Appalachia's special and concentrated on-going crises that take the intense forms that they do because mining and industrial Appalachia has functioned as a kind of "internal colony" within the United States. Anthracite is hardly used these days and the union-represented garment, textile and other industrial manufacturing are mostly gone and so the region is neglected and impoverished.

New immigrant labor in the region is exploited and faces discrimination not only from employers and political institutions, but from many of the descendents of the immigrants who worked in the mines and mills and who have been stuck there and whose lives are only marginally better than those of the new immigrants if they are better at all. The insularity and clannishness that Appalachia is known and harshly ridiculed for can be both a commonsense response to outsiders who often bring harm to the region and who also often disguise themselves as friends who are trying to help, but it can also be means of dividing people who objectively share long-range interests. Paul Shackels' new book

Ruined Anthracite: Historical Trauma in Coal-Mining Communities gives an excellent overview of these conditions and can be read along with Young's book.

Culm Bank in Beaver Brook, Pennsylvania, 2018. Credit: Paul Shackel

Young's book is filled with endearing recollections and tougher reflections that slowly and carefully build on one another in order to give readers an understanding of how values and world views were transmitted from adults to children in the anthracite region. The region was simply known as "The Anthracite" when I was young, and as the author points out the coal was "our coal" and people felt a defensive pride in their communities. "When all is still, when we're upstairs lying on our beds, we'll hear the coal trains rumble upgrade," Young says, "We know who we are. It's our coal on those treains.

Our coal. Our fuel to burn."

Young also remembers visiting a cemetery and says

Spread across the hill in small clusters, the gravestones mark households, naming those who lived together and leave spaces for those who will join them. Here we trace our names incised in gray granite. Our names: first and last, passed on to us. These are our uncles, aunties, and cousins in this fenced-in yard. They laid rails, blasted coal, opened doors to mines. They hauled and shoveled coal, and drank hard to blur hard living. Their hands pounded bread dough, watched it rise to pound again. They held their children in the night, feverish from influenza, dying from diphtheria.. And now they all lie, side-by-side, tiny headstones clustered behind large ones.

On this hillside the dead sleep. I imagine that their dreams drift down with the waters, float beneath the plank bridge, and past the tunnel. The quiet dances with the breeze that stirs and shakes the ribbons hung at each gravesite; the brook rolls over stones endlessly shushing, shushing.

But a train comes, breaking the stillness and the voice of the brook...

An aunt, a great-grandmother, my grandmother, and my grandfather.

Young also tackles how we came to understand something of our pasts, our relations, and Americanization in The Anthracite when she recalls her childhood confusion over when to use "Zi'" and when to use "Aunt" and "Uncle." The Italian words for "Aunt" and "Uncle" ---in my family they were "Zia" and "Zio"---were reserved for people born in The Old Country and the American words were used for relations born here, but these words were also used imprecisely. My Great Aunt Emma remains Zia Emma because she was born in The Old Country, but my Great Aunts Pally (Celeste) and Catherine were Aunt Pally and Aunt Catherine because they were born here. People we had no blood relationships with who were born here might also be called "Aunt Rita" or "Aunt Doris."

Young's memories and mine diverge on a few points, but I realize that the Hazleton area was different from Scranton in some respects despite their proximity and I trust her memory more than my own. She did not see photos of breaker boys as a child, but I certainly did. I don't remember coal trains hauling anthracite coal. Young says

It wasn't bad enough that our valley began emptying of people during the Great Depression and never stopped, or that the land was black while the rivers ran orange. It wasn't enough that smoke rose from the burning piles of waste coal lining the length of the Lackawanna River, and below ground, the mines caught fire. The air we breathed day and night was smoke-filled and reeked of the rotten-egg sulfur smell. The ornate nineteenth-century buildings, our fabulous city architecture, crumbled or mysteriously burned down. Around us everywhere were ill and unemployed miners, machinists, and factory workers. Sanatoriums topped the mountains---refuges for the wealthier members of the community with lung disease to escape the smoke for a while. Twice yearly, the Turberculosis Society van with its heavy x-ray equipment parked in front of our schools. We children entered it, and one by one splayed our chests on the screen to find out who among us were the next victims.

Breaker boys

While thinking about the differences between Hazleton and Scranton I recalled meeting a man in a church in Baltimore from Hazleton many years ago. I had guessed that many people from The Anthracite attended that church and I wasn't wrong. The man was telling me about his wife and mentioned that she was from Scranton. He then said somewhat wistfully, "Imagine that! A girl from up in the Valley would marry a guy from Hazleton! No one thought that it work out, but it did." The man and his wife belonged to the same ethnic group, attended the same church, and were both blue-collar people, but something still separated their communities.

I want to make three concluding observations here. Whether they intended to or not, it seems to me that the adults in the book were preparing Young for an adult life outside of the region. They often encouraged her childhood curiosity and intellct and they gave her the tools needed to succeed. Young implies this, I think, but she doesn't tell readers if this was the case or not. Second, I think that Young and I share the angst or survivor's guilt that comes with having left the region. There is much in the book about how she left, but there is less about why she left and about why she does not return.

Last, near the end of the book Young provides something like a land acknowledgement that mentions the Lenape people who were forced out of the region by white settlers and colonialism. This is welcome, and it could have gone into greater and deeper detail, but something else comes to my mind here as well. Today across much of Appalachia children will show up for holiday and other social events and go for the candy and presents or prizes, but it happens frequently that they also check to see where the Narcan is for the adults with them. "Look, Grandma, the Narcan is there!" you might hear a five-year-old shout. Young does a great job when she contrasts where she now lives in the Midwest with The Anthracite and when she recalls how people not from the region can be callous when they think about the region and our people. That critique is a necessary part of the story, but time is moving on and we have to see this new development as well. It is not only about mournig what we have lost and about defensively protecting our cherished memories and people, but also about seeing the next step being taken in the region's alienation and fighting back.

Note: Thanks to Charlie Stephens of Sea Wolf Books for recomending this book. Please see the Sea Wolf Books website for a list of their classes and retreats and to order books.